Carbon Dioxide in the Air - Evidence from the Ice

Ice cores are cylinders of ice drilled out of an ice sheet or glacier.

They are usually 10 centimetres in diameter, and can be taken from kilometres deep in the ice.

Most ice core records come from Antarctica and Greenland.

The longest ice cores are 3km deep.

The oldest continuous ice core records extend 123,000 years in Greenland, and 800,000 years in Antarctica.

Ice cores contain information about past temperature, and about many other aspects of the environment.

"Air bubbles trapped in ice are like little time capsules that record the past atmospheric composition," said Dr Emilie Capron of the British Antarctic Survey.

"So we measure loads of different gases and essentially we can measure greenhouse gases such as carbon dioxide and methane."

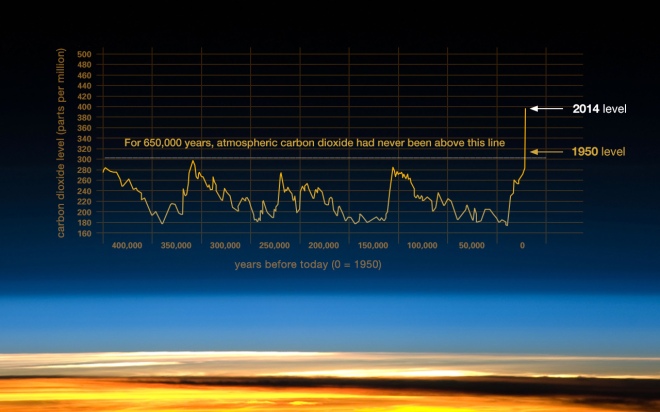

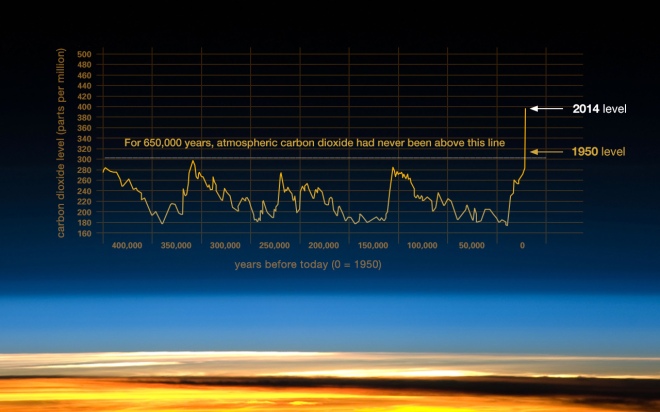

The graph shows how carbon dioxide has increased and decreased over hundreds of thousands of years.

The low readings match with times called 'glacial stages'.

During glacial stages, ice covered large areas of the Earth.

The peaks in the graph show times when carbon dioxide was high, matching times called 'interglacial stages'.

The most recent glacial stage occurred between about 120,000 and 11,500 years ago.

Since then, the Earth has been in an interglacial period called the Holocene.

During glacial stages, CO2 levels were around 200 parts per million (ppm).

During the warmer interglacial periods, they hovered around 280 ppm.

In 2013, CO2 levels passed 400 ppm for the first time in recorded history.

This rise in CO2 is caused by burning fossil fuels.

The last interglacial period occurred 129 000 to 116 000 years ago.

They are usually 10 centimetres in diameter, and can be taken from kilometres deep in the ice.

Most ice core records come from Antarctica and Greenland.

The longest ice cores are 3km deep.

The oldest continuous ice core records extend 123,000 years in Greenland, and 800,000 years in Antarctica.

Ice cores contain information about past temperature, and about many other aspects of the environment.

"Air bubbles trapped in ice are like little time capsules that record the past atmospheric composition," said Dr Emilie Capron of the British Antarctic Survey.

"So we measure loads of different gases and essentially we can measure greenhouse gases such as carbon dioxide and methane."

The graph shows how carbon dioxide has increased and decreased over hundreds of thousands of years.

The low readings match with times called 'glacial stages'.

During glacial stages, ice covered large areas of the Earth.

The peaks in the graph show times when carbon dioxide was high, matching times called 'interglacial stages'.

The most recent glacial stage occurred between about 120,000 and 11,500 years ago.

Since then, the Earth has been in an interglacial period called the Holocene.

During glacial stages, CO2 levels were around 200 parts per million (ppm).

During the warmer interglacial periods, they hovered around 280 ppm.

In 2013, CO2 levels passed 400 ppm for the first time in recorded history.

This rise in CO2 is caused by burning fossil fuels.

The last interglacial period occurred 129 000 to 116 000 years ago.

Climate information from the last interglacial period is particularly relevant.

During that time, temperatures on earth were higher at the poles than they are now.

The sea level was also between five and nine metres higher than current levels, because of the melting of ice in Greenland and Antarctica.

In the UK, the last interglacial period is called 'Ipswichian'.

Above, an interglacial 'raised beach' deposit at 9 metres above sea-level.

This pebble, shell and sand accumulation is "Ipswichian" in age.

The warming during the last interglacial period was due to natural causes, such as changes in the solar radiation hitting the earth due to the tilt of the earth on its axis.

However, because no previous climate has been affected by human influence, this earlier warm period is useful to estimate what the future has in store.

"We can use past climates as a natural experiment on the earth’s system to unveil the way it reacts and the way it works." said Dr Valérie Masson-Delmotte, of Institut Pierre-Simon Laplace, France.